2017 New year's Greetings and Message From the President

Dear Students, dear Parents, and dear Friends,

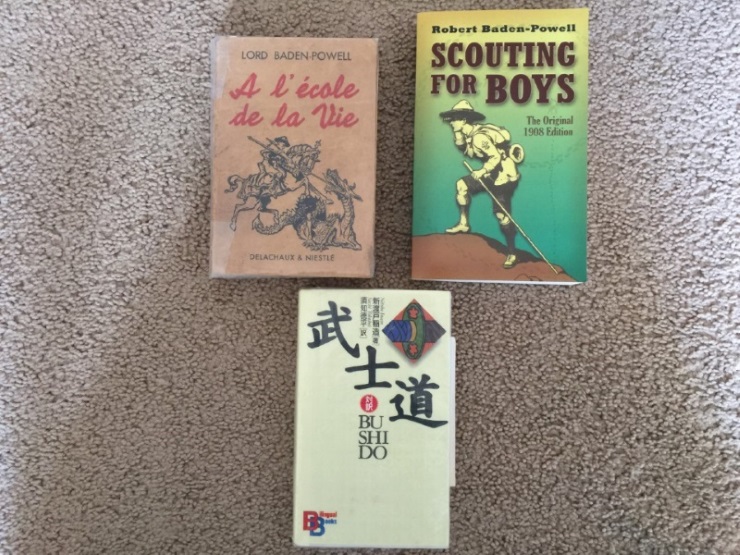

Another year has passed. I will turn seventy soon, and it will be fifty-eight years since I first stepped on a Jūdō mat in the basement of La Providence College in Amiens, France. The Dōjō was attended by many Boy Scouts, who learned and practiced Jūdō as required by Boy Scouts founder, Lord Robert Baden-Powell, in his book, Scouting for Boys.

My Grand Father, who had been my main mentor, had a French translation of Baden-Powell’s original 1908 edition in his library, and he gave it to me when I was twelve. That book had a major influence on the direction of my life. It encouraged me to develop the virtues of the knight in a modern setting, and Jūdō was part of that path. I knew that some of those Boy Scouts participated in Jūdō only in order to please the leaders of their activity and accumulate badges and promotions; however, I was mainly interested in forming relationships with those who were truly seeking to improve themselves while cultivating a spirit of chivalry in modern times.

To me, the objective of the study was clear: learn to overcome your fears so that you can defend yourself as well as come to the aid of those who are in need of help. Baden Powell recommended Jūdō – which was still referred to as Jūjutsu at that time – due to its emphasis on controlling the attacker without causing him unnecessary damage; thus, he deemed it the martial art of choice for the modern knight.

Because of that book and my Grand Father’s guidance, I wanted to join the Boy Scouts, but my parents opposed it; they worried that my commitment would take time away from my school studies. I talked to my Grand Father and to Father Hamelin, the priest in charge of the Boy Scouts in our school. Both of them came up with the same suggestion: “You can study and practice the Spirit of Scouting by yourself without joining officially…”

So, I decided to take the initiative. Some of my school mates with whom I had been hanging out were Boy Scouts – I would learn from them! I also took advantage of school pilgrimages to travel with them and experienced what they experienced. They also let me attend some of their activities in school and learn new skills, such as, camping equipment repair, survival techniques, and first aid, and I also attended lectures on how to cultivate the kind of spirit I had envisioned for myself and my community.

On this quest, the last hurdle to overcome was to be allowed to join the Jūdō Club, which again my parents opposed in spite of my Grand Father’s support. They knew my quick temper, especially when facing injustice and bullies, and they feared that I would use the martial techniques that I learned indiscriminately.

The opportunity for a decision came soon as the causes and conditions had been ripening. One day during recess, I saw Didier M., a well-known fourteen-year-old six-foot school bully, trampling on a smaller boy’s feet because that boy had not smuggled in his cigarettes as promised. Seeing no teacher or supervisor in sight, I approached and grabbed Didier M. by the shoulder, pulled him around, and punched him on his jaw. I knew that I had to do it quickly to deflect his attention from his victim and avoid a head-butt, his specialty.

We were near one of the entrances to the building. The door opened, and the Senior Father (the School Principal) appeared. He signaled for me to approach him. He said to me, “You must learn to control your temper! From now on, you will be practicing Jūdō during recess time!”

To my parents – particularly my religious mother – the Senior Father’s words undoubtedly came directly from God to save my soul and redirect it on the right path, so they instantly granted their permission! The teacher, Mr. Bitaille, was a former military officer, strict on etiquette and discipline – and he was exactly the kind of teacher I needed.

Thus began my journey into Jūdō. At that time, Jūdō was not an Olympic sport yet, so the mind-body connection and self-defense were still strongly emphasized. Competition was considered a part of training, not its purpose; it was a means to cultivate courage while overcoming our fears and making quick decisions while also respecting our opponent’s dignity and body. Our opponent had to be seen as a partner who helped us perform at our best. If a technique was done incorrectly and could cause injury to the opponent, the referee would not grant a point even if the technique resulted in a clean throw. In fact, so much emphasis was placed on safety and respect that any recurrence of an unsafe move would immediately result in “Hansoku-make” (defeat by grave infringement).

Thus, we all strived to practice correctly. Take a technique like O-soto-gari (major-outer-reap), for example. In a clean O-soto-gari, you gain leverage and unbalance your partner on his heels by placing your supporting foot on his front outer-side; then you strike his knee-crease with your calf muscle at ninety degrees with le line of his feet. His knee will bend immediately and safely. Your partner will fall cleanly for a full point (Ippon).

Unfortunately, rules have changed with the popularization of Jūdō as an Olympic sport and its control by foreign Jūdō organizations – in spite of Jūdō founder Kano Jigoro’s opposition to these changes prior to his death. In the case of O-soto-gari, for example, you may now attack your opponent’s knee laterally and force it to bend in that direction – a more dangerous stress on the body. It requires less commitment – hence less risk of getting countered – from the attacker; it also takes less unbalancing and more strength. But with constant repetition, this new development will eventually result in permanent injury to your partner; however, under the new rules, you will gain full Ippon if you manage to throw your opponent and make him land with impact on his back, no matter if he gets injured or not. This teaches practitioners that the ends justify the means – and the objective is to get your opponent (no longer your partner) on his back and for you to score the point. Dignity and safety are not necessarily considered.

As a result of those changes, regarding self-defense, grappling Jūjutsu took over, but gradually, it too has been turning into a sport in its quest towards Olympic recognition. So what is left? Mainstream Aikidō has become martial choreography. And MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) has become the form of entertainment that has been gradually replacing boxing and professional wrestling.

We can learn so much about chivalric living from Scouts training; however, like many valuable traditions from the past, this aspect of Scouts training sadly has been pushed aside. I have been asking Boy and Girl Scouts who attend the Dōjō about their Scouts training. Some admitted that they did not know Baden-Powell; those who did knew little about him besides the fact that he was the founder of the movement. According to them, most activities revolve around the outdoors, such as, survival, first aid, trekking, etc. – but they study and practice very little, if anything, about developing the knighthood spirit and training in martial arts. Those practices are out of the picture. Consequently, perhaps they compromise previous original aspirations, such as, service to community and connection to one another.

I remember a time when Scouts built hand-made crafts or baked bread and other ventures in order to raise money. I heard that they could not do that anymore out of fear of being sued if something happened to a customer. So what option do they have? They can only resell pre-packaged and finished products, a practice which opens the door to corporate greed since no donations ever stay anonymous; they are often seen as opportunities for promotion leading to gain. What lesson can the youth learn from that besides putting a dollar value on finished products?

I talked to Boy Scout leaders about this modern trend: some did not seem to be concerned; others admitted that, with the spreading of the movement, some values have been fading, but they were doing their best with what was available to them.

Our Dōjō continues to remain connected with the Scouts, though. In the last few years, we occasionally led one-hour Introductory Martial Arts classes for Girl Scouts at the Dōjō. My purpose has been to expose the girls to the realities of self-defense: that it takes determination and training to defend themselves, that there are no magic tricks to keep them safe, and that they can become strong while remaining feminine and attractive provided they are willing to put in the required efforts.

But I always thought that there was a problem: Who was teaching the class? An old guy whom they could hardly relate to!

So this year, to honor another request for training from the Girl Scouts, I decided to assign one of the advanced girls to lead the class, and I acted as her assistant. She immediately had the girls’ attention – they recognized that she looked just like they did, and they could work to become just like she was.

This is all part of our Budō study. A few weeks ago, Advanced Junior Students watched Kuro Obi, a Japanese movie about Budō Spirit. In the story, one of the characters does not hesitate to disrespect his teacher and use corrupt military officials so that he can establish his reputation as the best karate-ka in Japan. He admits that, while disagreeing with their activities, he has nothing to do with them but convinces himself that it is all right as long as he can use them. Eventually he becomes like them. Another character sticks strictly to the master’s instructions – “Never throw the first attack!” Later, he finds himself paralyzed in front of injustice; he realizes too late that a preemptive strike would have been the only way to prevent matters from getting worse.

Kuro Obi brings a deep message and food for thought. It exemplifies the “winning at all costs” attitude that has been pervading martial sports; it also promotes the commercialization and sale of black belts under the excuse that “that’s the way it goes or you cannot survive otherwise.” It illustrates the superficial attitude of those who claim that “one should not make a living by teaching martial arts” or that “competition is bad.” Without observation, reflection, and flexibility, we rigidly cling to destructive, often self-serving practices, maybe without even noticing, often under pressure from the prevailing forces – like the bullies in our world. And we just keep the cycle going.

Whether it is Jūdō, Aikidō, Scouts, etc., as long as something has value, it appeals to both those who are genuinely seeking self-improvement (Enlightenment) as well as those who are merely seeking materialistic profit (Entitlement). I do not think that corrupted and well established systems will change from the top as those who lead are in place and comfortable with their positions; likewise, change will not come from those who notice and want to change but are paralyzed by the first group and by the bureaucracy.

At this stage, change can only come from the bottom as each one of us does his/her part.

This is essential in these dark times when our attention has been constantly distracted from the important questions of life. I have been tutoring the youths to think deeply, to communicate openly, to take initiative, to lead the younger ones, and to reflect on their own thoughts, words, and actions. They are not used to that, so, as with all new and unfamiliar practices, it is challenging for them, and the tendency is to come up with shallow and stereotyped phrases that they have been exposed to by the adult world. However, they have many questions (on the meaning of life among all), and they just need to train themselves and develop the skills to express those questions and share their thoughts. Familiarization is the antidote to fear.

Baden-Powell’s book was the first book that deeply influenced my life, for it made me think about possibilities – for myself and for my world. I read it over and over again, and it prepared me for Bushidō, the book written by Inazo Nitobe, which I later studied while living in Japan. Some people condemned those books as nationalistic, therefore outdated, “the kind of thing that dragged us into the war!” However, if readers stay aware of the context in which those books were written, if we think deeply about how to apply those lessons of the past to the present times, we can find many applications relevant to today’s life.

A little while ago, I found 2016 reprints of Baden Powell’s book, Scouting for Boys, by Dover Publications and ordered several copies for Boy Scouts in our Dōjō who have been active in the Advanced Junior Group. I also ordered the last bi-lingual edition of Nitobe’s book, Bushidō (presently out of print), for older teenagers who have been raised in a Japanese environment for their study. We will use these materials for our monthly Mondō. I really recommend those books to those Budō students who are willing to make changes inside of themselves, which is the initial step before changing others.

Developing the next generation – that is my current mission. Personally, I do not see myself as a master – that was not my calling – but as a stepping stone for those who will come after me, already born or not born yet. Therefore, I have been making sure that my students get exposed through social media and other means more than their teacher. There is very little original and authentic documentation about most masters’ early education and training. This will pave the way to recognition for the future teachers as well as serve as a source of inspiration for their students.

I often tell those youths, “I will be reborn as one of your students, and I will be that one persistent student, who asks many questions. So you had better be ready for it! I am not joking!” So they must be prepared for students who are eager to improve themselves under their guidance and mentoring.

Kaoru Sensei and I wish you a Mindful, Happy, and Healthy 2017. And we renew our vows of our uncompromising commitment to continuing and developing Mochizuki Minoru Sensei’s teachings.

Patrick Augé and Kaoru Sugiyama

I would like to express my gratitude to Mr. William Brown for his kind help with the English version.

![[Menu]](../../jpg/headere.jpg)

![[Menu]](../../jpg/footere.jpg)